The tactility in Clark and Gibisser’s film, its poetic, sculpture-like aesthetics, the respectful, organically alluring cinema verité style, alongside the poignant critique of historical patterns of extraction, expropriation, and ownership, offer much more than a compelling documentary film with matter that matters. From the slow, tentative movements of human actors feeling their way through survival with experienced care, dignity, and inquisitiveness, to automated, machine-learned gestures coordinating motion efficiency in tempo, reminiscent of Ballet Mécanique (Léger, Murphy, 1923), the film creates a sophisticated universe for the exploration of varied forms of technicity, materiality and materialism.

Echoing elements of critical post-human thought and non-human centred forms of intelligence, the avant-garde filmmakers’ collaborative work, offers a highly original testament to the mechanics and machinations of it all; an eloquent critique of the structured, calculated connections between humans, their environments, non-human forms of life, coded machines, and deterministic processes.

The refined depiction of the above, through associative montage balancing pure realism with almost oneiric aesthetics, that are prevalent in Clark’s body of work, elevates the film’s nuanced critique to its true potential. Reflecting on the very essence of film emerging through a series of shots, A Common Sequence (2023) creates an interesting interplay between its subject matter and form; film’s inherent connection to technology and technics, the aesthetic expressions, and portrayals thereof. Captivating through and through, the film cuts through the complex subject in a poignant, endearing and honest way, nurturing aesthetic, meaning-making connections and difficult questions about the human condition in hegemonic and neoliberal capitalist contexts, that inspire thinking long after the film ends.

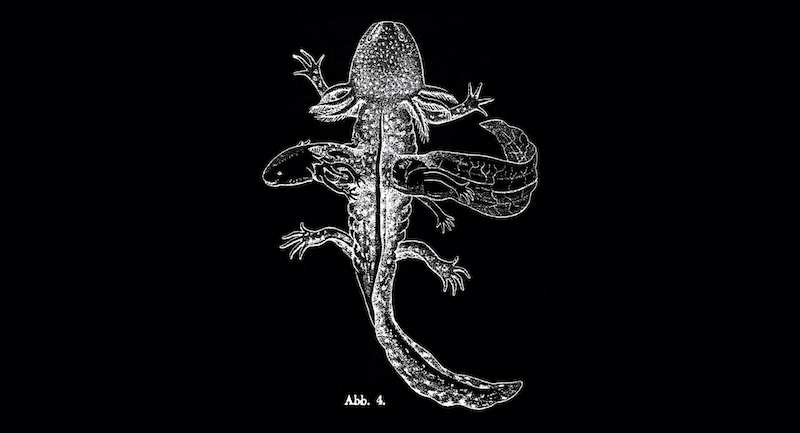

A cinematic process that focuses on groups, formations and ecosystems, A Common Sequence invites us to explore the raison d'être of interweaving threads of ownership and expropriation through what I would like to identify as a distinct post-human gaze. Under the latter, we observe an animated and timeless choreography in-between the agency of matter, humans and non-humans at the backdrop of hegemonic and neo-liberal capitalist approaches to the environment, communities and societies, whether analogue, or techno mediated. More than an observation through, it is a visualisation process paired with the sense of a reverse set of shots that does not register on camera but is rather imagined; the looming effect of sets of relationships and associations that exists no more, the shadow of formations or ecosystems that is strongly present in its absence. These dialogues formed sequence by sequence as the visible and its invisible reversal, form the very soul of the film. Historical practices of extraction and expropriation of indigenous land, the effects of the Anthropocene on biodiversity and natural resources, recent commodification practices of AI-infused, optimised agriculture and the possibility of commercialising human DNA through Genomics, all cultivate the ground for common sequences of discriminatory determinism to emerge. Following upstream the journey of a nearly extinct salamander in Mexico, the film unravels the multiple effects of human intrusion to their environment for profit, through interconnected stories; a group of fishermen struggling to live off a dying lake, nuns of the Dominican order who operate a local conservation lab, a group of scientists developing AI-led harvesting machines, and finally, the investigation of an indigenous biomedical researcher into the commodification of human DNA and possibilities for alternative propositions.

The muffled murmur of the water that softly touches the fishing boat in the opening sequence of the film, is only subtly heard, mostly felt owing to the patient, observant camera. The eeriness of the still night comes through the wonderful mise-en-scène and attentive sound design, but mostly through the juxtaposition of movements that develop in tandem with the pace of nature and its elements. The slow, meticulous movements of the fishermen’s hands going through their net in search of a rare salamander, seem to respond to invisible, inaudible movements of the achoque or axolotl and the gentle ripples of the water, in a respectful, natural choreography, as it were. What is it that we are looking at? What and who is it that we want to look at? Where do we want to place our focus on? What and who remains unseen but invites us to explore through full immersion in each sequence, frame by frame? There is depth and volume in the stillness; a sense of measured anticipation and potentially quiet resignation, as the fishermen’s lamps -the only point of lighting in the frame, warmly illuminate multiple pairs of hands tentatively feeling the rough nets. A static scene of life imbued with the transcendental mysticism of nature.

Renowned for its nutritional and healing properties for centuries- even before the invasion of the Spanish conquistadors, the achoque has been featured in science and history books and has been closely intertwined with the local lore. A source of income for the community, the salamander has been connected to the livelihood of an entire ecosystem of people, animals, plants, as food, medicine, opportunity for biological research. Its prevalence in the cohesion and growth of natural and cultural formations, traditions and local histories, bestowed a spiritual, supernatural almost essence upon the animal, evidenced through traditional songs and poems haling it as a hero. A victim of the Anthropocene or a strange turn of events owing to arbitrary human decisions in recent years however, the salamander has become endangered, almost extinct from its natural habitats, significantly altering the ways in which connections and ecosystems are formed.

Cut to Sister Ofelia, one of the Dominican nuns who run a conservation lab, a unit that farms the axolotl in a protected environment. It is her hands that touch the switch providing light in the room, but it is the affection in her demeanour and the ingrained faith in the animal’s potential to survive, thrive and offer its healing properties, that motivates her efforts towards its care. The bright light sheds clinical precision in the growth monitoring process enabled through clean glass tanks or small aquaria that crowd the spacious room in the old monastery. Sister Ofelia’s caring attentiveness, however, imbues the process with a notion of life-giving and life-sustaining domesticity, reminiscent of the nurturing care that newborns receive in their incubators. Extending a purely spiritual or ritualistic notion of the sanctuary as a process, or protection of life to its quantifiable iteration, the regenerative properties that are native in the precious salamander’s skin and body parts, will be utilised in the production of a cough syrup. Life will go on for the salamander, its essence, legacy, and association to a spiritual power nurtured and preserved centimetre by centimetre, whilst its body poses as a permanent exhibit of what was and what is; the life-forming connections of the past, their echoes through the transparent glass containers and their transmutation into the life-forming connections of present day. A new ecosystem of survival and domesticity is formed between the nuns and the salamander.

The chance encounter that never happened, the salamander never meeting the fishermen’s extended arms in the opening sequence, is juxtaposed with the eloquent articulation of mechanically orchestrated processes for produce growing and harvest collection. There is a peaceful rhythm, a gentle but determined, choreographed tempo as the pneumatic arm draws a set of careful, calculated lines of action while picking the fruit of human-computer labour; targeting the exact point at the branch of the tree, applying only as much pressure as needed to separate fruit from plant in an optimal condition for presentation and consumption, while moving at a speed 20% faster compared to human workers. With an ecosystem forming around the cultivation of original, patented varieties of apples, the fishermen move to Washington DC to join the local workforce. There is careful planning in the creation of a new variety of fruit, that isn’t reduced to conditions traditionally affecting agriculture, such as the weather, soil, watering, other plants or insects growing around it. And that planning is meticulous and original enough to warrant a patent. It is the mechanical arm that executes the interpretative dance of life-imbued code connecting the tree branches and fruit growing in the unseen grid, but it is the hands of human labourers and their movements that it has been modelled after, the hands of the scientists that calculated the optimal speed in which the arm needs to move, that provide the cues implicitly acknowledged in the process of the seamless move.

And the apple? In a fashion similar to the protected, clinical growth of the axolotl, it has been developing under human care and ingenuity ensuring that the fruit survives and thrives, looking its most marketable self. In contrast to the nuns however, their modus operandi has purely commercial goals and is recognised as an original, patented invention, a genetically modified crop that is owned by some human. The hand-drawn information, the sketches, the figures, the code; all the written material in its different formats presented in succession reveals the world, the ecosystem that lies beneath. Evidence of information and expertise is stored in timeless oral and written knowledge bases, yet it is all new or used anew in a modified ecosystem, as it were; in form, action, produce, approach to agriculture, common usage, property, exclusion, inclusion.

The third section unravels in-between the battle for self-determination and autonomy against hegemonic and colonial practices of othering and expropriation, in the present, data-intensive, inference-led neoliberal condition. Clark and Gibisser ponder over a possible, near-present dystopian idea of the commodification of the very structure of human life, that is our DNA, imbued with all the unseen historical and hegemonic disorders that belie it. With a focus on Genomics and the new frontier of mapping and extrapolating research and exchange value from human DNA, the filmmakers showcase this underrepresented aspect of the phenomenon of neoliberal capitalism forming around the data economy, or a re-capitalisation of the capitalist system around information, as sociologist Manuel Castells observed in The Information Age: Economy, Society and Culture (1996). While critical explorations of the evolution of this phenomenon have been presented both in fiction and documentary film, with The Great Hack (2019), Coded Bias (2020), The Social Dilemma (2020), being some recent examples, Clark and Gibisser’s premise hits too close home to our human core, in all its tissues, genes, cells… interlinked. The film sheds a light to a niche area of research, in a way that feels like a prescient meta-commentary to a dystopian future, as it were, that currently seems to be in the process of becoming. While similar themes have emerged prominently in the wider public debate through meticulous analysis of the facets of surveillance capitalism (Zuboff, 2019) technofeudalism (Varoufakis, 2023), data colonialism (Couldy and Mejias, 2019), and the perpetuation of discrimination and racism by code (Benjamin, 2019), the impact that an assetisation process of the human genomic sequence, its privatisation and potential use for predictive medical, societal and political decisions affecting communities and groups that have been historically othered or discriminated against, remains within disciplinary discourse in a restricted mode of view, as it were. A Common Sequence opens up this niche field of research to a wider audience.

There is a sense of eagerness, anticipation cutting through the quiet days in Dr. Joseph Yracheta‘s lab. A pair of precision and attentiveness, the Genetics researcher’s hands form a protective arc as they carefully touch the microscope, zooming in the human matter of DNA. Excited to delve into the unknown of the research process, his micro-movements reveal a strong sense of integrity and care, as his words fill the room with facts and academic rigour. The empathetic camera movements stay with the researcher as long as necessary, switching to a series of static points of view, courtesy of a zoom call. Director of the Native BioData Consortium, Dr. Yracheta calls for attention to the brave new world of assetisation of biological matter, and the risks it poses for descendants of indigenous and Native American people. With particular genetic characteristics or traits, such as resistance to certain bacteria or viruses, acquiring a whole new meaning in this context, the scientist and his colleagues call for a more equitable course of action. Pondering over concepts of human, non-human, collective, artificial, intelligence and knowledge acquisition, critical issues of responsible data stewardship, fairness and inclusion in data mining, processing and inference-generation processes, the scientist calls for practices that respect and acknowledge the values, traditions, culture, approach of indigenous and native populations.

Clark and Gibisser delve into the heart of the matter, beyond a meticulous documentation of recurring circumstances that allow certain patterns of expropriation and exploitation to emerge. Through an original approach that is porous and multi-layered, they create a nuanced piece of cinema that comprises an intriguing vernacular for the identification and visualisation of types of power dynamics, social and political inequities embedded in the patterns studied, alongside the potential for artistic experimentation. In this manner, facets of the aesthetic vernacular relating to film form emerge organically in-between sequences; a collage of sophisticated visualisations of rigorous investigation, as it were, though a lens of care that is only possible through cinema. There is a softness, tenderness but also precision to the explicit and implicit expressions of such vernacular that is heartfelt and precious, non-intrusive and aesthetically captivating, all the more emphasising the culminative effects of historically embedded notions of hierarchy, exclusion and expropriation of nature and the nature-culture continuum. The film form seems to be expanding its own boundaries to encourage new types of aesthetic and meaning-making connections.

Self-reflexive, the film ponders over its own affective and meaning-making potential, its original formal structure as a coordinated assemblage of narratives, aesthetics, frames and shots, that fold back onto themselves to present alternative or additional views, entry points to the stories, aesthetic iterations of the subject matter, sequences and the filmmaking process itself. The filmmakers, identify and actualise brilliantly a potential inherent in cinema that is all the more essential in the present-day profitable instrumentalization of techno-deterministic approaches to ecosystems. The filmmakers’ intention to showcase a critical genealogy of ownership, value-creation and expropriation by allowing the complex entanglements among nature, culture, societies, politics, humans and non-humans to speak for themselves, encourages an intriguing and unique cinematic vernacular to emerge organically; a comprehensive aesthetic and meaning-making proposition, that applies equally to the nuanced exploration of the subject, as well as the material and immaterial matter of the filmmaking process itself. The meaningful connection of various forms of entanglements between humans, non-humans and the film itself, ranging from the actual film shots, still images to historical hand-drawn illustrations, data and machine visualisations, comprises a unique exploration of the processes that cinema can encourage. The porosity of the film world, the liveliness of pauses, the depth in stillness and respectfully observant camera creates the necessary space for Clark and Gibisser’s particular post-human gaze to emerge organically in-between humans, non-humans, material and immaterial matter; relations or connections to others, documents, written code, technological artifacts, ethical codes, sets of values and principles, as well as the agency of spectator to identify and connect with the above during the viewing process and long after the credits have rolled.

By Eirini Nikopoulou.

Info:

A Common Sequence. Year: 2023. Written and directed by: Mary Helena Clark, Mark Gibisser. Countries: USA, Mexico. Languages: Green, Spanish. Duration: 78 minutes.

The documentary film A Common Sequence (2022) was screened in selected UK cinemas as part of the BFI London Film Festival in September 2023.