One’s first, visceral, affect-ridden response to the film may be similar to having been punched in the stomach; by pure cinematic force. A force that is poetic in its harshness and whimsical in its rawness, fully embodied in the outburst of a shirtless, tattoo-clad Barry Keoghan singing on top of his lungs: “Is this too real for ya?”.

Keoghan speeds down a main street in Kent, with his electric scooter; his teenage daughter, played beautifully by newcomer Nykyia Adams, standing right behind him. As the Fontaines DC song plays loud through Keoghan’s speakers and is being gradually morphed into a new artistic expression, it also serves as a playful reference to Arnold’s unique style of contemporary social realism. One that I would like to identify as her own unapologetically visceral and deeply cathartic social realist film world, that lusts for new life. A film world that is not merely observational or directly political, but one that emerges through the challenges of a situated quotidian experience to find love, hope, empowerment and a future in a hopeless place; to appropriate Rhianna’s lyrics and the way in which they were visualised in American Honey (Arnold, 2016). This combination of hurt expressed in multiple scales from offense to abuse, is expanded and explored even further in Bird, through the lead characters’ need for hope, and escapism, imagination and transcendental states of being. What is real? From which point of view is this expressed or affirmed, felt and seen? Who gets to decide how real this is? And if this is indeed real, who bears it and really wants to be part of it? Elements of escapism and magical realism are being intertwined with a harsh context of being, and becoming of age in clearly defined places, alluding to the possibility of ambiguity and contingency; the political being personal as one chooses the perspective through which they approach life and the challenging world.

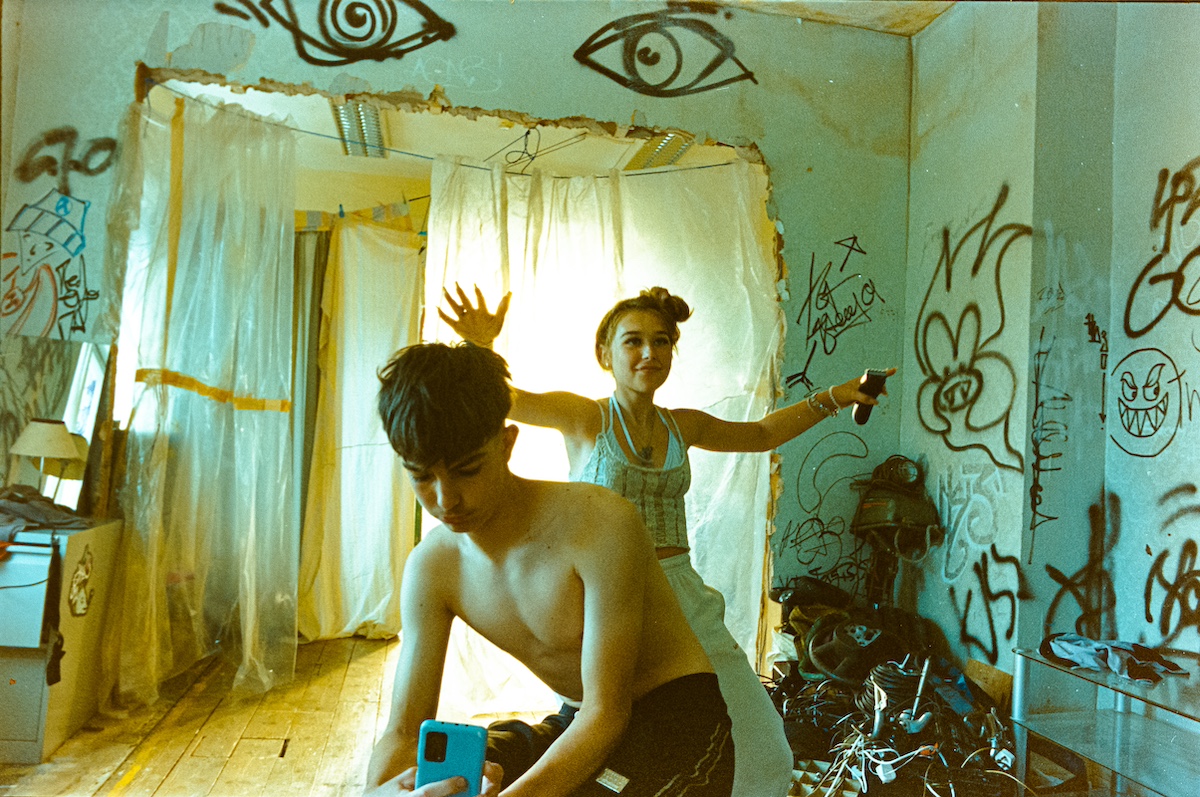

The handheld camera follows the days in the life of teenage Bailey, in a quick, energetic pace that opens the film with such spontaneity and vibrancy, that feels in synch with the characters’ movements; as if borne out of a perfectly choreographed ensemble. We follow the twelve-year-old as she walks fast through neighbourhoods in Kent, crossing bridges, bumping into friends and her father, running up and down the stairs of a squat. She lives there with her father Bug (Barry Keoghan), and the idiosyncratic family unit he created, comprising his fiancé and her daughter, his son Hunter from a previous relationship, and various friends who frequent their premises. Bug’s own expression of an entrepreneurial spirit or, what he calls his “dream”, pushes him to invent new, unconventional, often illegal ways of making a living that require time, effort, creativity and experimentation. Also, a lot of support from his family and friends. Bailey is left on her own devices to explore the world around her and grow up. She likes to wander around the city, follow her brother and his friends, and see life through the lens of her phone camera; capturing the moments when butterflies fly through her half-open window, and rest on her hand, reflecting light and life on their wings. She then watches the recordings on a make-shift projection space in her bedroom in moments of tranquility, as if to identify the freedom and beauty she had recorded. Bailey also likes to film real-life moments that feature the people around and near her; people she knows, people she would like to know and people that she, or the loose group of friends she calls her gang, would like others to know about, by exposing their actions. What does she think of them? How can she confidently communicate what she thinks, without being misunderstood? How can she ensure that she is being heard? Her camera serves as a natural extension of her vision and voice, as an amplifier that maintains her original point of view without any distortions. It captures her reality, or reality from her own unique point of view. The latter is something that she is called to explore in depth and potentially communicate its nuances as it becomes updated to resonate with life experiences that are part of her personal journey towards adulthood.

Enter Bird, played by Franz Rogowski. A stranger who dresses, acts, moves and talks unconventionally. He seems to be balancing in-between worlds, in-between lines of thought, in-between forms of perceiving, sensing and experiencing the world. He seems otherworldly, pure and quite perceptive, wise in his own way. He seems to need nothing; substantial nutrition, warm clothing, or sleep seem to be irrelevant details to him. He only seeks his family members from whom he has been estranged. He encounters Bailey in the middle of a field, and they instantly connect in a shared moment of carefree bliss. She offers to help him and from that moment on, their paths become intertwined. She meets him again in the town centre. She can’t help but stare at the unlikely spectacle he makes as he courageously balances on top of a building; his slim, fragile body moving back and forth as he readjusts his position for stability, almost as if he were moving with the wind. He gazes at the opposite building, peacefully, observing the people passing by in the street. However, he seems to be fixated on a single point. How did he end up here? What happened to him and the people he used to call his family? He is looking for what used to be there, what is currently being eclipsed, missing; almost as if he tries to bring his memories to life, to re-enact them. In doing so, he quite unexpectedly helps Bailey through her own journey, one of self-discovery and coming of age. While he focuses on what is missing from his life and relationships, he helps her navigate all that fills hers; her connection to her parents, their social circles, her siblings, her friends, environment and the city she grows up in. This intriguing oscillation between the present and the past, the explicit and the implicit, and the obvious and the unseen serves as a powerful motif in the film, operating on multiple levels. The unlikely friendship between Bailey and Bird serves as a catalyst to expose how reality can bite and hurt, challenge the notion of unyielding certainty, and begin reclaiming a balance in power dynamics. All that is implied is brought to light, and all that is hidden is fully uncovered.

Bailey takes Bird to her mother, believing she might be able to help him. What unfolds next—intense and graphic scenes involving her mother and three younger siblings—takes both Bird and spectators by surprise. These events set off a chain reaction, ultimately resolving the harmful power dynamics that have long shaped their painful realities. For Bailey, the deeply ingrained imbalances she had been observing around her begin to dissolve, giving way to new perspectives and reconceptualized ways of being and connecting. This transformation allows life, love, and hope to permeate her world. Similarly, Bird finds the answers he was seeking, liberating himself by acknowledging what was, what is, and what could have been, finally leaving the past behind.

Arnold does not shy away from the raw, grotesque, and often abusive realities that define her characters’ daily lives. Through gritty details of repetitive physical and emotional abuse, she captures lives that are difficult to endure—yet her characters have no choice but to survive, escape, or persevere. This unflinching portrayal is profoundly impactful, especially in an era where the connection between spectators and cinema, or other visual arts, is often contained through measures like direct and indirect trigger warnings, which aim to shield spectators from challenging material. Arnold’s work reminds us of the importance of feeling, even discomfort, as spectators engage with difficult themes—a pathway to catharsis that has stood the test of time since its initial conceptualisation in Greek tragedies. More importantly, the filmmaker achieves this emotional release through remarkable cinematic skill, allowing her unique sense of social realism to emerge and expose the uncomfortable truths we may prefer to overlook. Bird exemplifies the power of cinema to create a transformative space between the work itself and the friction it generates in its viewers. Arnold shows us how this friction can shape a cathartic journey, turning the raw material of pain into something deeply meaningful.

The social realism that Arnold presents in Bird, isn’t didactic. Through a compelling interplay of surveillance and sousveillance, she invites us to reexamine how we know what we know about challenging themes such as abuse and its various facets—issues we may have grown complacent about. The film pushes us to confront uncomfortable truths, exposing graphic scenes and prompting us to question our role as bystanders. What can we discover or unlearn? How can we change? In an era where domestic, physical, and emotional abuse —and even torture—are revealed daily across the globe, Bird offers a nuanced perspective, forcing us to see what lies beneath the surface. It challenges us to look up and ask: Who is watching, seeing, hearing, and caring? Who notices what exists in plain sight, despite being hidden, and who chooses to ignore it?

Arnold presents a compelling, universal story that, while situated in a specific context, transcends time, location, and social class. She encourages spectators to actively engage with her film through visual and thematic representations of surveillance and sousveillance, which permeate the entire film and create connections with her previous work (Red Road, 2006). We are encouraged to look up, follow her characters through trajectories that are essentially mapped on air; they cross bridges, run up staircases, tread on rooftops, move in great speed giving a sense of upward and forward movement; also, a sense of momentum that culminates to an actual or imaginary point of disappearing in the distance. Bailey meets friends, runs to her mother’s bedroom and looks up in the blue sky for a chance encounter with a butterfly. Bug speeds up on his electric scooter, nearly bare, giving the impression he might take flight. He is free, singing his happiness aloud and experiencing the world around him in a rush of vivid colour and exhilarating speed. Bird, likes to stand on rooftops and seems uncomfortably comfortable to watch others from above embodying a pure state of temporality; how long can he keep standing there before he eventually makes a calculated or impulsive move? We are watching Arnold’s characters move away, claiming their distance from a fixed point, as if they were trying to escape, fly away or appearing to contemplate how to do so.

But what drives their need to keep moving? Arnold consistently intertwines the act of surveillance—both literal, from above, and as a form of control—and sousveillance, the view from below, revealing how these contrasting perspectives can unravel complex narratives. Through a mix of handheld camera work, which follows characters during moments of movement and transition, and more stable shots that capture the stillness of emotional moments or realizations, Arnold creates a meaningful interplay between a fixed point of view and its challenging alternative. More importantly, she invites us to consider what remains unseen—the unseen consequences of an oppressive reality and the potential effects of practicing sousveillance.

By giving her characters the agency to capture and document their own and others’ lived experiences through multiple points of view, Arnold opens up a meta-commentary on how various perspectives can inform reality and influence actions. For example, Hunter "is doing business the old bill should be doing," as his young girlfriend, Moon, describes it. Bailey, on the other hand, sees the potential benefits of this approach in escaping the harshness of others' choices—choices that could impose a rigid reality on her and those around her. Yet she chooses to explore alternative ways of seeing: methods that integrate ambiguity and empower imagination, counteracting the harshness of predefined power dynamics.

Arnold’s compelling universal story, however, doesn’t imply a broad consensus on how aforementioned power dynamics can be shifted. Rather, I believe, that it incorporates a subversive approach to what may constitute a common understanding of reality; the extent to which reality and the nuanced facets thereof can be experienced in the same way by people, have the same impact and also how this can be changed. She distinguishes between multiple perspectives and approaches to what lived human experience may mean. By introducing an oscillation between surveillance and sousveillance, she opens to notions of spontaneity and playful exploration of the underexplored. This approach includes affect and the unexplainable ways in which one single moment which exists outside reality might also form a reality, either momentarily, through emotionally charged responses, or through the gradual introduction of something or someone new, that leads to a shift.

Arnold’s social realism blends appropriate doses alluring surrealism and imagination with unexpected intervals of innocence, optimism and joy. The successful integration of such moments depends largely to the wonderful performances by the entire cast. Nikya Adams in the role of Bailey, fully embodies coming of age, or passage into womanhood with the contained fragility, tenderness, curiosity, denial and consideration of situated gender stereotypes. If what means to be a woman is closer to her mother’s experience, then she would rather experience another reality which allows her to choose how she relates to others and others relate to her. Barry Keoghan affirms once more his expressive versatility, dexterity and investment in the character he embodies, so much so, that Bug becomes him, and he becomes Bug. He generously offers refined texture to Bug’s coarseness, allowing softness and a certain warmth to come through, that provides essential space for optimism, associated with new life, to take root and sprout. Franz Rogowski works wonders as Bird. He floats; he passes through spaces, interactions and dynamics in a state of composed, structured fluidity. He embodies beautifully what is and what is meant to escape, in a heartwarming and gently manner.

Arnold, allows flexibility to a possible escape from the inescapable, offering organic, spontaneous moments of joie de vivre. Bug’s incurable optimism, his love for music, his fiancé’s happiness on their wedding day, Bird’s almost supernatural abilities, and Bailey’s immersion into his world—all serve as light-hearted expressions of hope. And this is in my opinion Arnold’s unique take on social realism, which embodies the rich tradition of the genre in all its nuances yet alludes to a voluntary departure from a reality which her characters have to deal with. From open vistas, views of the streets, people, houses, creating the conditions for one’s empowered despite their age, Bird is infused with all those too essential moments of clarity, empowerment and joy in finding oneself and actualising one’s potential in living life most unconventional, yet inspiring in its brief but meaningful moments of true empowerment not only in relation to the self, but also to one’s perspective on kinship, love, and hope. Also, the invaluable dedication to allow our gaze to wander beautifully until it reaches that moment it lays on what it sought in the first place. In this sense, Arnold’s film world is, in my opinion, close to the work of other talented contemporaries of hers, such as Alice Rohrwacher (Happy as Lazzaro, 2018 ; La Chimera, 2023), who has drawn on historical incidents that undermined and oppressed entire communities, to showcase the possibility of an alluringly surreal, whimsical process of counteracting even the most harmful effects; a process that identifies an opportunity for hope and the beauty of life amidst chaos.

The mere juxtaposition of multi-layered expressions of the rawness of lived experience intertwined with appropriate doses of appealing transcendentalism, or magical realism, can have a strange effect; one that only good cinema can produce on multiple levels and the sort that Arnold's signature aesthetics have proved to express with such beauty and integrity. Who is part of a hurtful reality and who is ready to incorporate healthy touches of surrealism or escapism to re-imagine their experience and re-position themselves? Visually arresting, with captivating performances throughout, this coming-of-age film bursts with life that is equally enticing, intriguing and meaningfully triggering, serving as a reminder of all the possible ways in which spectators can connect to a film and a film can connect to spectators. Does that mean that one may exit the cinema room with more questions than answers? Perhaps. But isn't this what cinema is all about? Arnold invites the spectator to be an interlocutor in this film by choosing which types of connections they form with the challenging themes she presents in this film, among a range of multiple options, types of abuse, expressions of mental and emotional resilience. Most importantly though, how these can be overcome through a beautiful tapestry of vulnerability and kind empowerment, in a process of life growth and maturity. This, perhaps, marks Arnold as a great filmmaker and Bird as a much-needed film that’s been missing from our screens for far too long.

By Eirini Nikopoulou