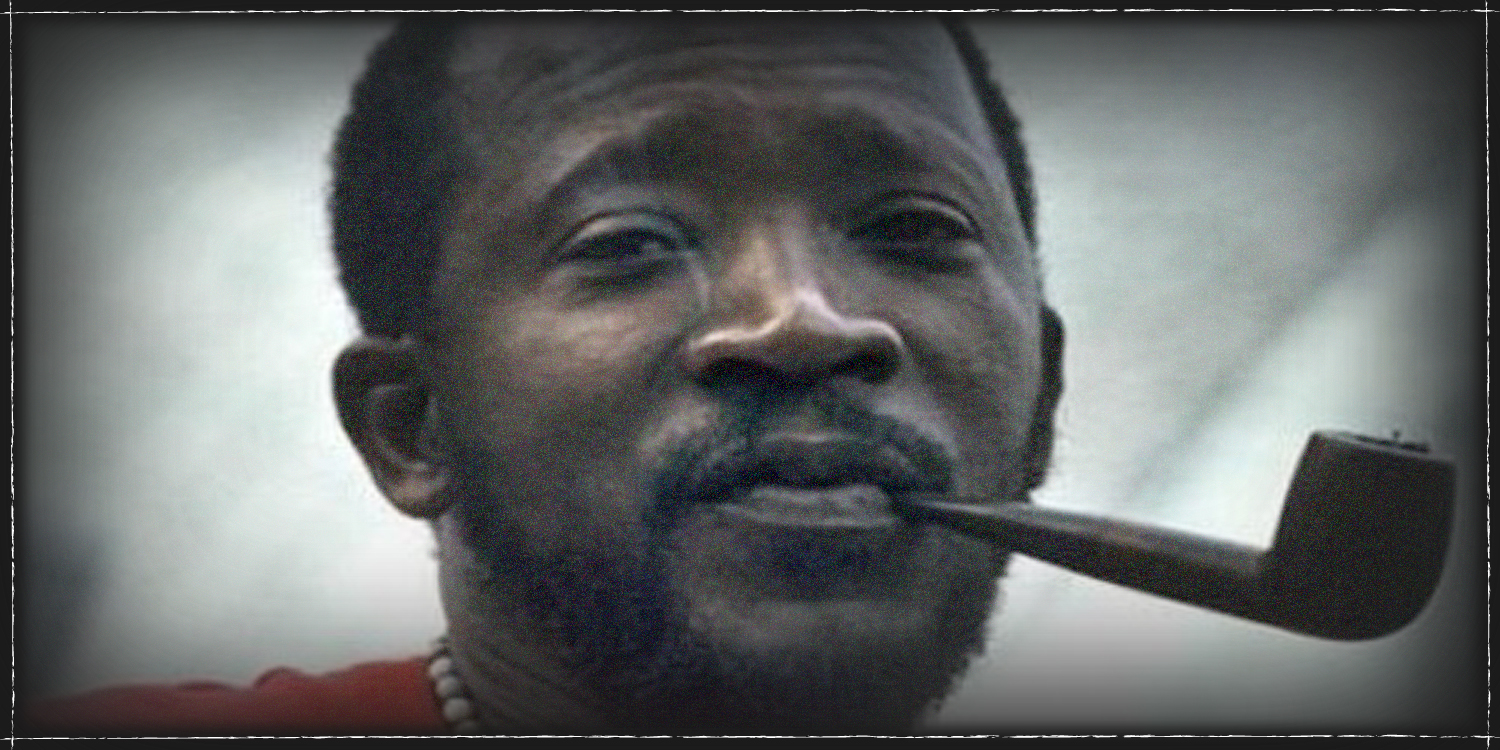

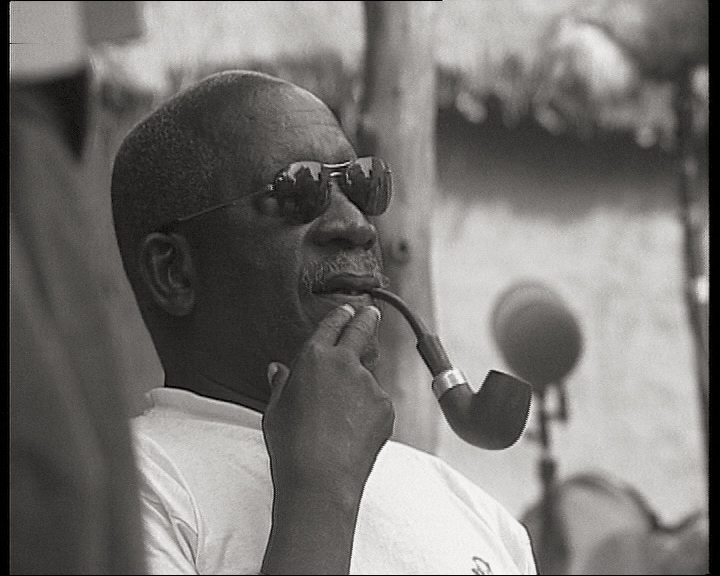

We often hear the term "Father of African Cinema" associated with the great Senegalese author and filmmaker Ousmane Sembène. Indeed he is today recognised as an outstanding post-war African filmmaker, his work studied and taught universally- no genuine film academic or cinema historian can boast of never having come across his oeuvre during the course of their own research. Of course this is entirely due to the paucity of Africans that have worked in cinema and thus Sembène stands today as almost the sole historical black Sub-Saharan African progenitor and therefore representative of the global medium of cinema, who now, a hundred years after his birth, is to be honoured with a much deserved and necessary retrospective, courtesy of the British Film Institute (BFI Southbank) in London, one of Europe's leading film institutions.

There were other filmmakers before him, such as much respected self-taught painter and actor, Albert Likeke Mongita from Democratic Republic of Congo with his 1951 information film, La Leçon de Cinéma (The Film Lesson); and Guinean writer and director Mamadou Touré, who made Mouramani in 1953, a 23 minute drama largely credited as having been the first African film with a black African at its helm. The missing print of this film is the subject of a recently made documentary, The Cemetery Of Cinema (2023) which competed at Berlin this year, directed by film academic Thierno Souleymane Diallo who travels across continents tracing the film and its history, but ostensibly exploring the lack of film appreciation and distribution facilities in his home country, Guinea, but one can certainly expand this to Africa as a whole. And one cannot underestimate Paulin Soumanou Vierya, first director of the Senegalese Newsreel Service, who also made films in the mid 1950’s, including Afrique-sur-Seine (Africa on the Seine) in 1954, a film recounting the lives of African students in Paris. A film historian, producer of more than thirty films- mostly newsreels- commentator and tremendous advocate of African film, Vierya became an increasingly important supporter and was instrumental in ensuring Sembéne’s career trajectory. And this, while operating under the egregious decree of French Vichy minister Pierre Laval who sponsored and passed a law banning African film content and more perniciously, African filmmakers in the French colonies from getting behind a camera until 1960 when this erroneous dictat was overturned. So when all is taken into account and we explore the simplistic beauty in and of Ousemane Sembéne’s work as a dramatic filmmaker, he appears to transcend all geographical computations, becoming just simply a gifted intellectual and artist. Yet despite being greatly respected in the faculties of ethnographic universities and film societies Sembéne is largely unknown outside academic circles.

Sembéne’s humble beginnings speak volumes for what he eventually would achieve in the course of his life. It is said at the age of thirteen, he was expelled from his French speaking school for striking a teacher. Whether there is validity in this account remains questionable but what is not disputed is that from a young age he worked with his fisherman, father while also doing manual labour until the outbreak of World War II when he would be drafted into the French Army.

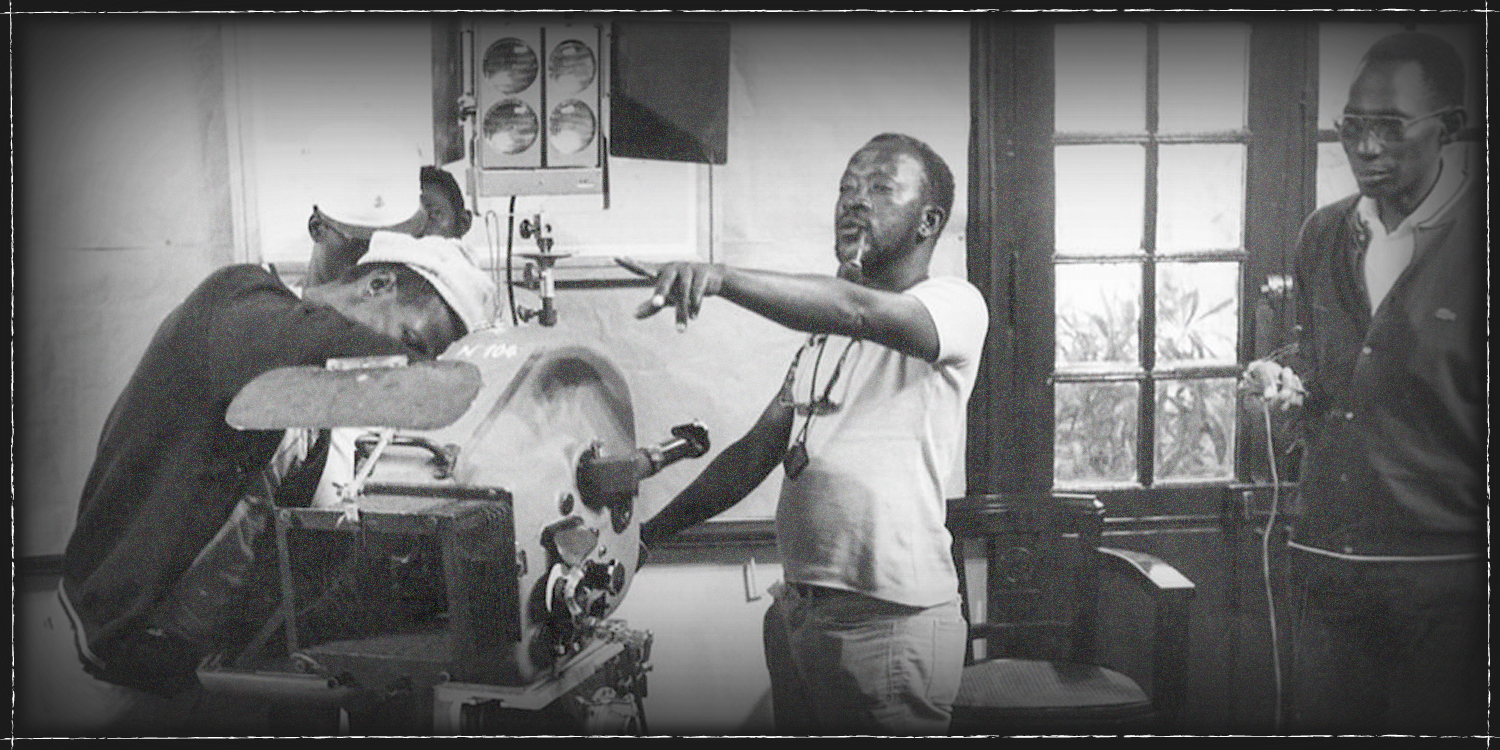

At the war’s end Sembéne returned to Senegal (where it was also rumoured he was given a dishonourable discharge for insubordination) but, as like many young men who had served overseas, he soon migrated to France seeking adventure and finds work on the docks of Marseille where he joins the Dockers trade union and teaches himself to read and write French, eventually, or inevitably, becoming actively involved in the dock workers’ struggle for better working conditions. At that time it would be hard to conceive that Sembéne could have escaped the swirling discourse on African independence amidst the heady transformative atmosphere of the ‘Harlem Renaissance’ that erupted from black academia in the 1920’s. In fact, in the late 1930’s one of the leading proponents of the movement, celebrated Jamaican poet and author Claude McKay, who was accused of being a communist had lived in Marseille for a time before being deported. It wasn’t long before Sembéne officially joined the French Communist Party and became fully involved in activism on behalf of his colleagues but a serious back injury confined him to hospital and it was there while recuperating that he decided on writing his first novel Le Docker Noire (The Black Docker) 1956. More publications followed, such as Les Bouts de Bois de Dieu (God’s bits of Wood) 1960 and Xala (Impotence 1973). Yet despite relative international success he was acutely aware that class and illiteracy limited his reach amongst African people and he began to think of cinema as a way of addressing this. With support from the union he travelled to the Soviet Union to study filmmaking and returned determined to tell stories of African people to African people.

His first released film Borom Sarret, (The Wagoner) 1963, an 18 minute short documenting a day in the life of a wagon driver as he struggles to make a living in the city of Dakar is an immense introduction to a filmmaker’s canon. Apparently using short ends and discarded film stocks, a borrowed 16mm camera with non professional actors on a minuscule budget, Sembéne’s cinematic potential could never be doubted. The wagon driver’s need to make a living balanced against the poverty in his beloved new country is engrossing. The interactions with the local Senegalese community is at once, rich and diverse, such as his encounter with a disabled beggar and the subtle emotion of the pregnant woman who leans her head gently on his shoulder as he takes her to hospital. At one point he takes a passenger with a dead baby to the cemetery for burial only for the bereaved father to be barred entry due to bureaucracy. The cold practicality of a growing capitalist system sees the driver place the dead child at the grieving father’s feet so to make himself available for his next passenger. However the driver’s joy at encountering a religious storyteller to whom he chooses to give his meagre earnings, forces him to then take the risk of driving into a restricted area to inevitable consequences and the feeling of shame that follows. The wagon driver returns home empty-handed, minus his cart, confiscated in lieu of the fine. It’s rather telling that in the end it is the woman, his wife, who leaves ensuring him the family will eat that night. And one believes they will.

The complexity of the Wagon Driver’s first person narration is translucent in its depiction of the times and the author’s own sensibility but was received by some critics in typical colonial fashion, a paternal dismissiveness. But the truthful dignity evident in Sembéne’s characters was recognition of the growing reality of a newly independent nation after a century of brutal colonisation. It is the dignity borne of being in charge of one’s own destiny, doing what one chooses to do, right or wrong- the wagon driver knows he could be prosecuted if he drives into a restricted area but he chances it anyway. The power of the personal choice is ordinarily missed or misconstrued by hegemonic western observers but Sembéne’s view is one of an objective reality as demonstrated by his debut feature film La Noire de… (Black Girl), 1965.

A beautiful young African girl who dreams of living in a European country gets her chance when she is offered the chance to be a nanny to the children of a French couple. However her dreams are shattered when she finally migrates and finds herself trapped in the prison of servitude - her cultural identity, heritage and freedoms stripped away. The subject and treatment of this evocative film, shot mostly in southern France, is restrained and even paced with a remarkable performance from Mbissine Thérésé Diop in the title role, marking Sembéne as a filmmaker who cannot be placed in a colonial box. The narrative is prescient and highly relevant in a way that is startling to audiences today. At the time, critics pointed out that the Madame was unfairly depicted, having no redeeming qualities. However, it is easily contended that any redeeming quality from Madame ended the moment she began to resent and undermine the young, beautiful woman she lured from Africa and then sought to enslave, albeit unwittingly (unwitting in as much as it pertains to a systemic hegemony) and without remorse. The Monsieur’s depiction was less critiqued, most probably due to his almost aloof attitude and at the last, attempting to return the Black Girl’s belongings to her family in Senegal, including an African mask, a gift Madame and the Black Girl had previously fought over. It’s revealing that when he tries to leave the mask follows him - a reflection of the guilt that stains the European coloniser perhaps? In any case, he runs rather than face up to his complicity in the events that led to the tragic outcome.

Sembéne was a visionary filmmaker. Yet the critical response to his work at the time suggests that a latent psychological restriction is placed on African art that, even today, emanates from the hegemonic exhausts of colonial racism in automatically assuming that art from other cultures has less value than western European art. But Sembéne managed to radically disturb that mode d’emploi through his forceful and belligerent posture on his work and intended audience. As a post independence African filmmaker he was able to turn his gaze inward, toward the newly interred policy makers in Africa who maintained a top-heavy European standard of governance on their unsuspecting populations. His extraordinary film Mandabi (The Money Order) 1968, is a humorous and yet exquisite study of capitalism across cultures when an unemployed villager receives a money order from Paris.

Ousmane Sembéne passed away in 2007 at the age of 84 and it is to be noted that this giant of African cinema had almost single-handedly put Senegal at the centre of African film, challenging the impact of the northern African colonies’ long history of film dating from the turn of the century. Of course, these films were ostensibly French films shot in the territories using the landscape and the people as backdrop to French narratives. Sembéne leaves a legacy of social political cinema that needs to be more widely seen by audiences, particularly so they can appreciate and understand how colonialism has and continues to affect the continent. One cannot fail to hear the chorus of voices painting Africa as the next economic power, a continent with the fastest growth in the world today. Yet in truth, is this really the case if Africa struggles to come to terms with itself as a continent of black peoples? Or is it that the land-grabs and divisioning of the past 500 years continues unabated under the cloak of diverse modernity while those from the east and west devour it from within? Who knows? Ousmane Sembéne knew.

Which brings us full circle. If Ousmane Sembène is supposedly the Father of African cinema why is it that he and his films are unknown outside of academic circles?

How do we find a way to decolonise his work and increase the debate in African societies?

Perhaps a fanning of the flames on discussions around a pan African digital distribution network is required to challenge the economic dominance of the western streaming giants with their plush tower block offices to make room for an alternative African-led network that allows for proper archiving and commercial access to important African film content... say, an African Film Institute or Academy funded by the individual countries themselves that will embody education, history and distribution?

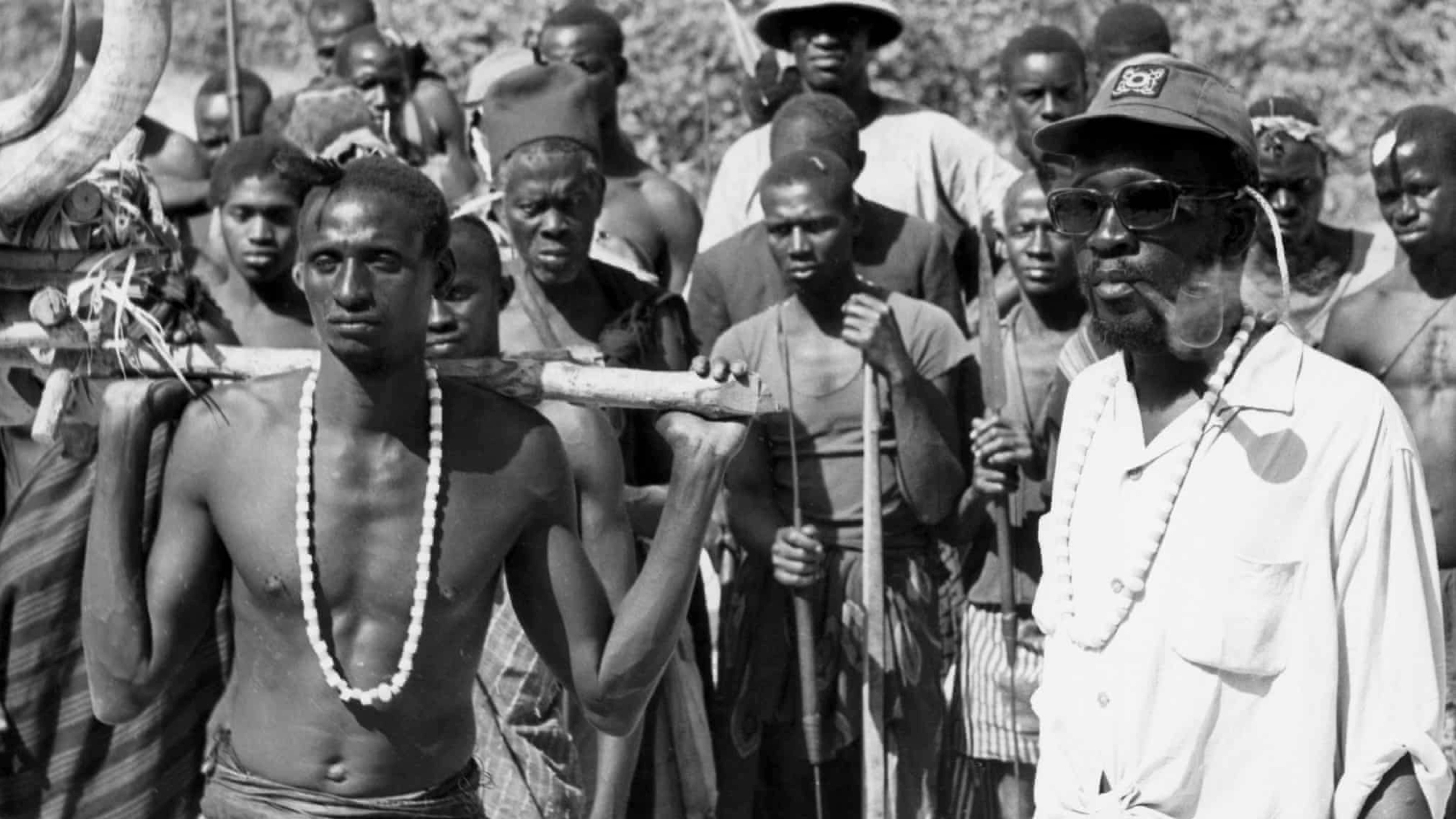

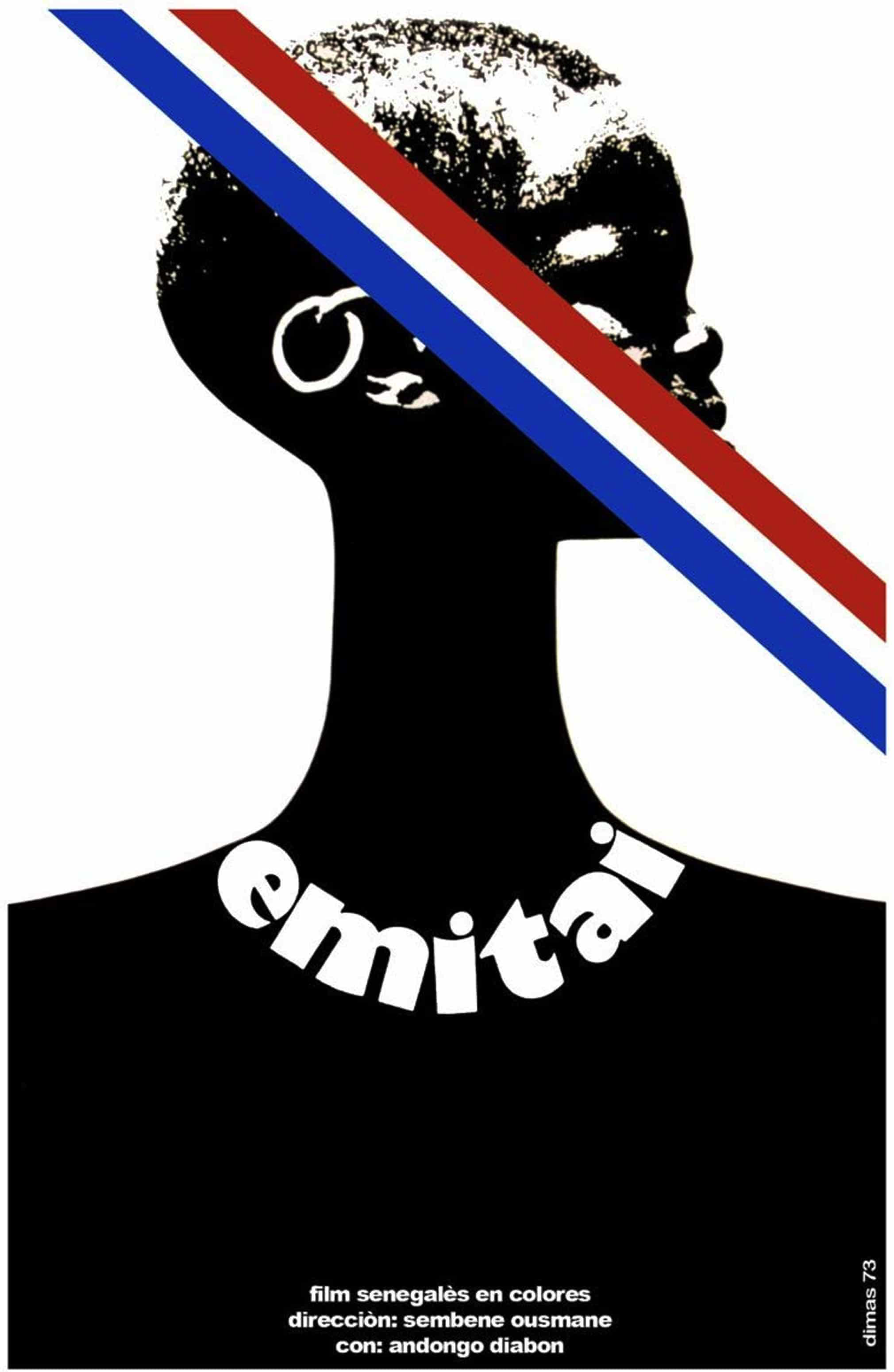

In the meantime, during the month of August BFI Southbank, London screens a retrospective of Sembéne's restored films. His shorts, award winning and celebrated works are included, among them his debut feature film La Noire de… and his banned socio-political films such as Camp de Thiaroye, banned in France for over two decades, Emitaï, banned in Senegal for a time due to its anti-colonial tax stance- Sembéne did however, arrange a special screening in the Guinean bush for the celebrated pan African revolutionary freedom fighter, Amílcar Cabral and his guerilla fighters who, at that time, were engaged in a brutal, decade long war against Portuguese colonial rule- and also in the programme, the controversial film Ceddo, censored across most regions of West Africa for its examination of the historical conflict between Islam and Christianity on the continent. See links below for further information and screening times.

REBEL CINEMA OUSMANE SEMBÉNE AT 100

REBEL CINEMA OUSMANE SEMBÉNE AT 100

August 1, 8

La Noire de… (Black Girl), 65 mins, Senegal/France, 1966 + Niaye (1964 short)

August 4, 19, 23

Mandabi, 92 mins, Senegal/France, 1968 + Tauw (1970 short)

August 4, 26

Emitaï, 103 mins, Senegal/France, 1971

August 5

Sembéne! 89 mins, directors Samba Gadjigo/Jason Silverman, USA (2015)

August 5, 26

Ceddo, 120 mins, Senegal/France, 1977

August 6, 20

Camp de Thiaroye, 153 mins, Senegal/Algeria/Tunisia, 1988

August 7, 17

Guelwaar, 115 mins, Senegal/France/Germany/USA, 1992

August 9, 26

Xala, 123 mins, Senegal, 1968 + Borom Sarret (1963 short)

August 23, 30

Faat Kine, 120 mins, Senegal, 2001

August 28, 30

Moolade, 124 mins, Senegal/Burkino Faso/Morocco/Tunisia/Cameroon/ France, 2004

Mark Norfolk