A special presentation at the 66th BFI London Film Festival, Ruben Östlund’s Palme D’Or-winning feature film has spectators still navigating their way out of a triangle of wry humour, the currency of allure, and reflections on that thin line between the cynicism of abuse of power and what a potential re-distribution of power can lead to.

Making the most out of his distinct, sardonic-observational gaze, as I would describe it, that established him as a promising filmmaker of his generation, the director of Force Majeure (2014) and The Square (2017) delivers an intriguing instalment in his unofficial trilogy.

As in the previous two works, Östlund uses wit, skill, and aesthetics of realism to create a nuanced, tangible depiction of a particular status quo, formed on the basis of convenience, established gender, class and power dynamics or just sheer absurdity. He then uses this as the premise of his film-world and starts dismantling it by infusing chaos and anarchy, showing what can be done when the blown-up pieces are collated in new formations. Does the experiment work, though? An intriguing and witty film through and through with the appropriate notes of dark humour, Triangle of Sadness draws spectators in, long after they exit the cinema room. The only thing preventing the film from fulfilling its true potential of becoming exquisite, is the excess or overindulgence in plot points cramming too much in, or showcasing how wide a range vulgarity can have, alongside raw aesthetic choices which tamper with the film’s rhythm making certain sequences, particularly in the third part, feel unnecessarily long and less refined in comparison to the first two. Still, Östlund’s work stands out and the film creates a unique, anarchic cinematic experience well worth delving into, particularly for his attempt to create a film-world dismantling and reconstructing dynamics of power and control throughout.

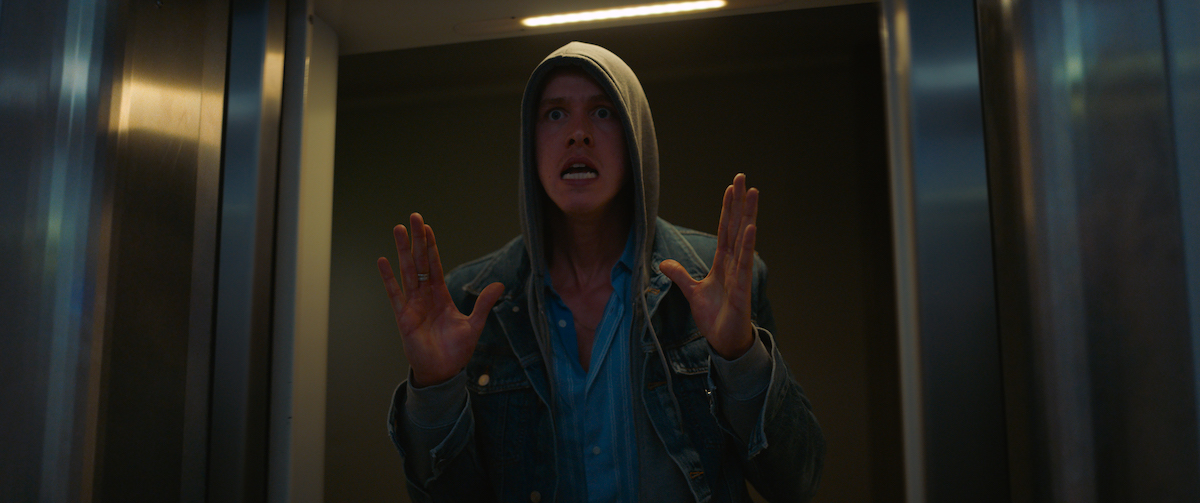

Opening with a group video interview of models identifying as male who audition for a fashion show, the film establishes its own aesthetics of realism and sarcastic, idiosyncratic world right from the outset. It is through the lens of the handheld camera that we are introduced to the models’ commodification of allure, precarious working conditions and entrapment in a triangle of sadness. A life less instagrammable in other words for the professionals who identify as male and earn a third less than models identifying as female, while having to navigate their way through a neoliberal-infused mainstream that uses their financialised allure as a double-edged sword; a form of currency that can both empower them to walk the luxury catwalk of established fashion houses, but also objectify them and make them vulnerable to fashion industry professionals who make inappropriate advances towards them. “Can you relax your triangle of sadness, please?” a casting director advises Carl, the protagonist played by Harris Dickinson, during his audition. It is the tension, anxiety and built-up helplessness in the area between his eyebrows that make his commodified currency prominent. To make matters worse, it is also the deep knowledge he has no way of taking back control.

Carl appears to completely vanish in his little triangle of heavy feelings when his partner Yaya, beautifully played by the tragically lost Charbli Dean, who identifies as a female model enters boisterously the scene. The currency of allure they both share acquires a completely different dynamic in the relationship between them; the potential for emotional manipulation or the perception that the other can have that power over them. Both survivors of a neoliberal-infused assetisation of their personas, they develop a transactional relationship that looks good for business and on their personal feeds. There is some type of love there they both admit, but what kind of love that is depends on their clout. They fight over splitting the bill at a fine dining restaurant with Carl insisting on all things and payment being equal, they fight over Yaya staring at a bare-chested crew member on board their luxury cruise, their fight over Carl using his currency or allure to survive when the ship goes down.

Their love story and different exchange rates of their currency unfold on the deck of a luxury cruise ship which hosts all possible manifestations of richness, from monetary to privilege-related but also to notions of survival. Carl and Yaya are surrounded by Russian oligarchs, a quintessentially British elderly couple who despite their comme-il-faut attitude they made their fortune based on arms sales, and all the unseen labourers whose wealth derives from their mere existence, that is, the survival skills they had to develop throughout their lives. This unlikely melange becomes more nuanced when political theory is introduced to the mix, with inputs from a Marxist, utopian captain with addiction issues, brilliantly played by Woody Harrelson and a neo-liberalist Russian oligarch who grew up during the communist era. The nouveau-riche, the traditionally rich, the intellectually rich, the rich in survival skills and all the stereotypical connotations that come with these notions of wealth, are brought on board. Tension rises when the captain’s seven course dinner turns sour, and guests have to surrender to their seasickness rather than the pleasures of fine dining, while the ship is going down Titanic style, but in a far less glamorous mode.

What follows next seems to be taken out of survival-themed reality TV shows. The well-heeled guests alongside few crew members find themselves ashore a deserted island with very few supplies of Evian water, having to fend for themselves. With Abigail, the housekeeper, being the only person, whose survival skills can help everyone find and prepare food, all types of interactions, transactions and currency exchanges are in place in order to manipulate or coerce her to provide for everyone’s sustenance. It is at that point that Abigail, brilliantly played by Dolly De Leon, asserts her power and the tables turn, hierarchies are re-established, as she makes her own rules in this temporary equilibrium. Until balance changes once again and a chain of events re-establishes the previous status.

One of the things that glitters and is gold in this film, it is certainly the performances by the main characters, particularly by Dolly De Leon and Woody Harrelson, and of course the two protagonists Chabli Dean and Harris Dickinson who are naturally and effortlessly brining their characters to life reinforcing the reality-style aesthetic proposition of the film.

With excess being a focal point in this film, multiple worlds and expressions of the concept are represented in excessive sequences, as it were, that are so nuanced, detailed and affect-ridden that come to occupy the film itself. Some sequences feel sometimes as a portmanteau film on their own, with the connecting thread being the excess or overindulgence in visual representations, dialogues, plot points particularly in the second and third parts of the film. The long sequences of designer dress-clad seasick guests drowning in misery, for example, feel a bit stretched sometimes, an overindulgence in the vulgarity and pointless vanity of the uber-rich. Even though poignant it feels somewhat exploitative as it aims to elicit an immediate intense reaction by spectators. An interesting choice for a film addressing the issues of use and abuse of power, this feels like a self-reflexive expression of its themes, as the filmmaker and editor decide to weaponise the power of the cinematic means in excess in order to achieve that. While the intention and effort is commendable, the aesthetic result can feel a bit distasteful. Also, the interactions and exchanges between Carl and Abigail on the island, appear too repetitive and a bit sketchy. Once the point has been made, the repetitiveness of similar scenes seems to be flirting with reality TV aesthetics rather than cinematic expression.

The variations on excessiveness seem inexhaustible in this film, with the multiplicity of themes expressed being a prominent one. Gender dynamics, expressions of matriarchy, patriarchal traditions, old money, new money, hierarchy, discrimination based on class, ethnicity and nationality, capitalism, Marxism, communism, neo-liberalism are some of the themes the film is dealing with. Again, the intention is noble, and, in most scenes, the poignant humour and great performances are contributing greatly to the cause. However, the mere premise of having these ideas presented in excess of themselves doesn't allow them to develop to fully and makes their connections seem somewhat convoluted.

Despite these minor flaws, the Triangle of Sadness is a genuine anarchic comedy which stays with spectators long after they exit the cinema room, for all the good reasons. It complements Östlund’s unofficial trilogy beautifully and proves the versatility and skill of the promising filmmaker.

By Eirini Nikopoulou.

The film is shown in UK cinemas from this week and one should get caught in it while they can! More info about screening times: https://www.curzon.com/films/triangle-of-sadness/HO00004187/

Info:

Director and Writer: Ruben Östlund. Cast: Woody Harrelson, Harris Dickinson, Charlbi Dean, Zlatko Buric, Arvin Kananian, Henrik Dorsin, Iris Berben, Oliver Ford Davies, Shaniaz Hama Ali, Sunnyi Melles, Malte Gårdinger, Hanna Oldenburg, Carolina Gynning, Camilla Läckberg, Dolly de Leon. DOP: Fredrik Wenzel. Produced by: Philippe Bober, Erik Hemmendorff.