- What matters?

- The truth.

- Who says what truth is?

- I, I, I !

This casual conversation between painter Kurt Barnert, the protagonist of the film, and his artist friend Günther Presusser (Hanno Koffler) during their studies at the Düsseldorf Academy of Arts, could have been edited as a short clip, capturing the entire essence of the film. Nothing matters more than what the artist feels and expresses as truth and no person or official structure can legitimise or validate that notion of that truth adequately enough, except for the artist themselves.

The proof, as with most things, being in the artwork. Delivering a visually arresting film which features some compelling performances and an outstanding music score, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck affirms this concept for himself, too. There are certainly some flaws mainly to do with the central performance and convenience features in the script, which don't allow the film to reach its true potential. Nevertheless, Never Look Away is well worth watching, as it is a tender and masterfully crafted cinematic experience about art, life, history and humanity.

Inspired by the life and oeuvre of Gerhard Richter, one of the most important living German artists, the film is an homage to the personal life experiences which influenced and formed his art, style, personality and character at the backdrop of the most critical socio-political transitions in modern German and European history. Spanning three distinct historical periods the film unfolds in corresponding chapters, reflecting the artist’s childhood in Nazi Germany and early influences from the "Degenerate Art"; his adolescent years, early adulthood in the German Democratic Republic and exposure to Socialist Realism; his marriage, move to Düsseldorf and influences from avant-garde movements, such as Fluxus.

As a young child Kurt (Tom Schilling) experiences his father loosing his teaching job for not being an active member of the Nazi party, his beloved aunt Elisabeth taken away to an institution by the Health Authorities, the sense of desolation after the WWII. His natural talent in painting and connection to the liberating force that his artistic expression enables him to embrace, seems to be the only thing that keeps him going. Rather introvert and restricted in his expressive means when he interacts socially with other people, Kurt seems to be utilising his pencils and paper, canvas and brushes as actual extensions of his body to really communicate with the world around him. His life reaches a turning point when he meets fellow Arts Academy student, Ellie (Paula Beer) and falls in love with her. Their whirlwind romance, which is not approved by Ellie’s father, a former high ranking SS obstetrician, becomes the catalyst which enables both his personal and artistic development to begin. Despite professor Seeband, his father in law’s objections, Kurt marries Ellie while climbing the ladder of success, as one of the most prominent artists of Socialist Realism.

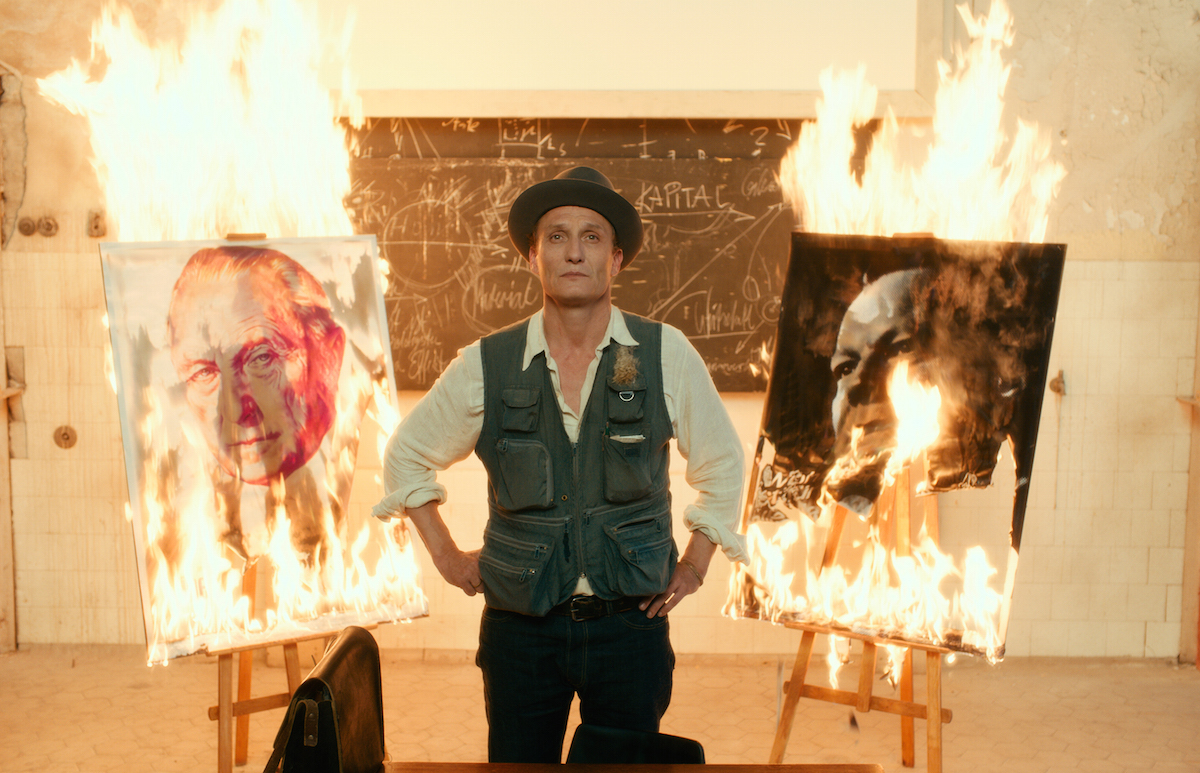

Nevertheless, he soon realises that he needs to escape the confines of the German Republic of Germany (GDR) in order to fully explore his artistic potential and so he and his wife decide to defect to the West, right before the construction of the Berlin Wall. Their move to Düsseldorf, his studies at the at the Academy of Arts under professor Antonius van Verten (Oliver Masucci), a character inspired by professor of Monumental Sculpture and renowned artist Joseph Beuys, proves to be a decisive step towards Kurt finding his own style and voice. That newly found sense of freedom also establishes an interactive feed between his now materialised artistic persona and his past experiences, family life and subconscious realisations.

Unbeknown to Kurt, he and his father-in-law shared a special but horrifying connection. Despite the fact that this is not clearly depicted in the film or expressed by Kurt, his work serves as a second narrative level disclosing disturbing information. Almost as if his paintings have a life of their own, they form a series of encoded messages which, when put together, reveal the string of connections, associations and hidden truths influencing the decisions of all characters. Assisted by the mesmerising cinematography of celebrated DoP Caleb Deschanel and the exceptional use of light, which make each scene reminiscent of a painting, the narrative levels blend into one another comprising a harmonious storytelling showcase. Additionally, the sublime music by Max Richter featuring variations of tender subtlety and also more emphatically expressed, almost triumphant tones highlight ideally each narrative feature, resulting in this epic film about art.

Loyal to his principles of extensively researching his subject, Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck does not only try to recreate period features but most importantly the “feel” of each era. On that note, there is something to be said about the outstanding performances by some of the cast members which make this “feel” authentic. Oliver Masucci, Paula Beer and Sebastian Koch in particular, stand out. Masucci plays the role of professor Antonius van Verten brilliantly. He delivers the part with emotional gravitas, ferocious mystery and seductive simplicity culminating in the pièce de rèsistance of the film, the scene in which he visits Kurt’s studio.

Paula Beer’s performance is great, bringing Ellie from screen to life with equal amounts of subtlety, introspection, wit, emotional depth and attractive vivacity. Despite the fact that the character seems to somewhat fade in the background after a certain point in the film, Beer maintains a compelling presence throughout proving that she is definitely one to watch in the future.

Koch, who already created a long lasting impression to international audiences as the writer Georg Dreyman in The Lives of Others, is exceptional in the role of professor Seeband. He showcases incredible dexterity in expressing the entire kaleidoscope of personas which the conniving master of disguise, professor Seeband, asserts for himself. A true believer of the Nazi Eugenics and broader ideology, which he reveals or hides according to the environment he finds himself in, he manages to create a convincing profile of the loyal husband, loving father, law abiding citizen and maintain his status as a decorated doctor across all three periods examined in the film. In that sense he is the epitome of the distinction among truth, truthfulness and truthiness, or what appears and feels as true even if it isn’t necessarily so, which permeates all narrative levels of the film and is expressed as the polar opposite of Kurt’s journey through life.

The latter, played by Tom Schilling is a journey towards freedom, liberation and truth. Utilising fragments of truthiness relating to himself, his life, art and others around him he goes through a process of self-discovery in order to crystalise that truth he discovers, in his art. With an internal, almost distanced performance Schilling allows the story of an art student, en-route to becoming one of the greatest living German artists, to emerge from an observer’s point of view. This quality the filmmaker tells us, resonates with Ulrich Mühe’s performance of the Stasi agent Wiesler in The Lives of Others. Despite talented Mr. Schilling’s effort however and not having a single ounce of doubt that the filmmaker had the best intentions in mind when he decided to direct he lead actor in such a way, there is a feeling that the attempt doesn’t quite reach its full potential.

Intriguing though it may seem to have the lead character observing himself as an outside person, so as to fully express the notion of “Work Without An Author”, there is a sense of void; a feeling that something should be happening, but it doesn’t. While the late Ulrich Mühe as agent Wiesler would mirror the physical movement, emotional state and even elements of the socio-political stance of the people he observes and empathise with them, Tom Schilling as Kurt Barnert mirrors everything in his paintings, on a second narrative level, and never gives his feelings and thoughts away; almost as if he is trying to become a blank canvas himself. While both characters are reminiscent of a Bresson type of model, Ulrich Mühe delivers it much more successfully, achieving great engagement with his exceptional, internalised performance. On Tom Schilling's case however, even through the use of this type of model is interesting as an intellectual exercise it falls short of the connection the audiences are expecting to establish with the lead character of a film of epic proportions, such as Never Look Away.

Nevertheless one is willing to forgo this alongside some other flaws, mainly to do with convenience the script, in order to fully appreciate one of the most interesting installments in the depiction of art on screen. The character of Ellie seems to be somewhat underdeveloped with important plot twists, involving her directly, being introduced in the second and third part of the film rather sketchily. This is rather disappointing particularly after a strong start, a brilliant first part of the film and the high expectations one has of the filmmaker and all the inter-textual connections to his outstanding first feature film. Never Look Away however manages to stand out as an important piece of work, as it poignantly embarks on a fascinating journey to the truthfulness of art and its transformative power on the self, collective subconscious, humanitarian ethos, culture and society. At the same time it skillfully draws a distinction between the liberating force, which art as a catalyst helps individuals and society to embrace, and the controlled interpretations of it which certain truthiness-clad (post-truth) societal and political structures would have them believe in order to promote various agendas. For that reason alone it is a must-see.

By Eirini Nikopoulou.

Never Look Away is released in UK cinemas on Friday 5 July.