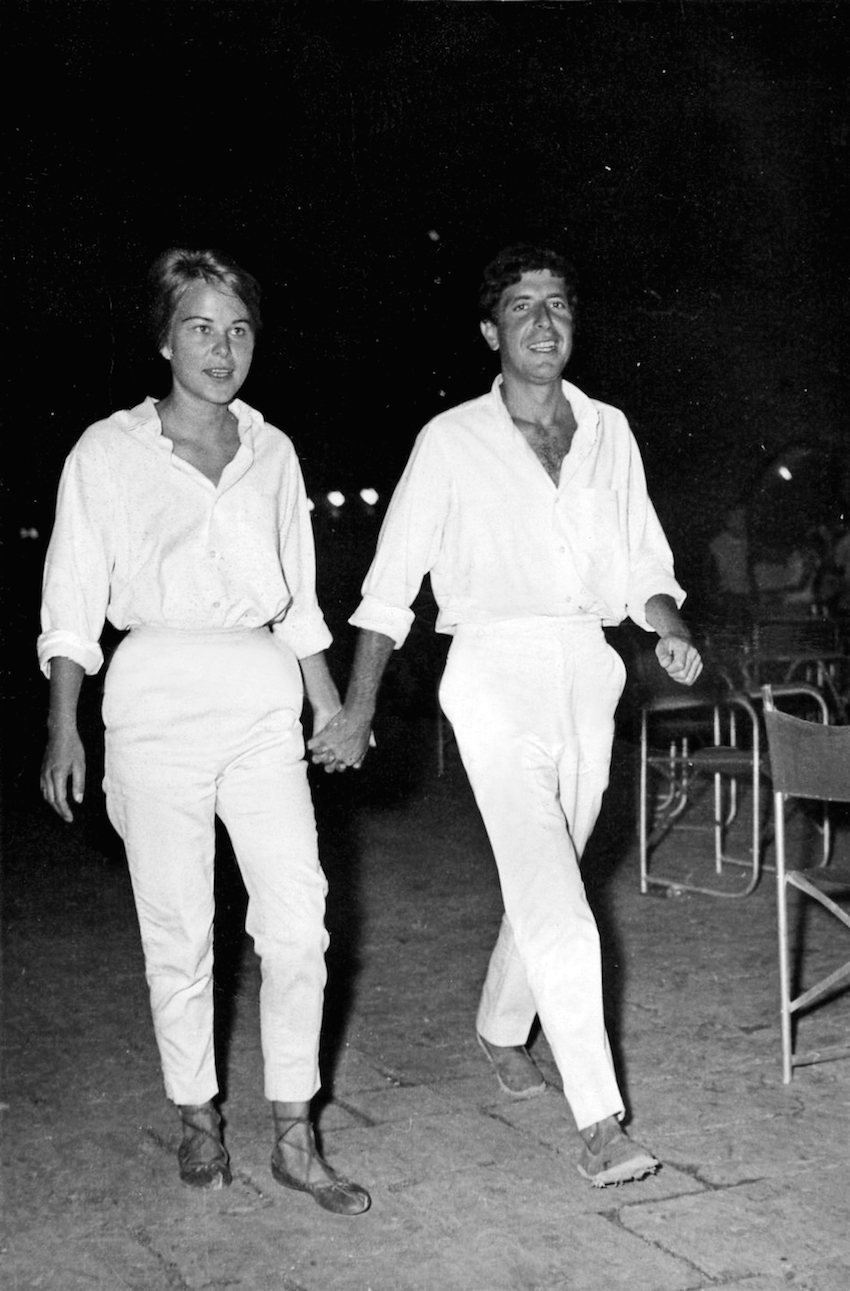

A tender, intimate portrait of Marianne and Leonard, through their formative years, the becoming of the artist Leonard Cohen and creative Marianne Ihlen, their owning up to their definition of love.

Nick Broomfield’s candid narration of his personal experiences and relationship with Marianne and Leonard, which are interwoven with archive footage, interviews, and still photos, is the force elevating the film from the status of a standard biopic of an internationally renowned artist and his muse, to a kaleidoscopic experience of their personalities, art, creativity and emotions, with the 1960's zeitgeist and the island of Hydra acting as unseen characters.

The film starts with an account of Broomfield’s first encounter with Marianne on the Greek island of Hydra while he was still in his early ‘20s, their brief love affair, which clearly had a long-lasting impact on him and the friendship they forged for the rest of their lives. Clad in previously unseen footage of Marianne Ihlen, shot in the 1960s by D.A. Pennebaker the narration has a gentle and personal tone which occasionally seems like a confession or a carefully penned love letter which was never sent. Unconventional it may seem that Broomfield utilises his own personal experiences and feelings right from the outset of the film, essentially injecting himself into the story, it is actually a clever move to represent the timeproof, whirlwind romance between Marianne and Leonard in the most engaging way. It is through the impact they have on others that the personalities, influential power and connection of the two characters become crystallised. The true nature of their relationship however remains elusive even to Broomfield himself, who occasionally appears puzzled and surprised by the strong bond and affection growing between the two friends of his, despite drifting apart, separating for many years and inflicting multiple wounds upon one another.

Marianne Ihlen moved to the Greek island of Hydra with her first husband, the writer Axel Jensen and their six month son, also named Axel in the 1960s. Part of a larger movement of international artists and creatives settling to the almost primitive island, which at the time had no electricity, running water or landline phones, they developed a community fostering artistic exchanges and creativity. Heavily influenced by the youth counter-culture and social movements of the ‘60s, the majority of the members of this community espoused the lifestyle of open love and polyamory, as well an acid-fuelled expression of artistic creation. When Marianne and her husband divorced she decided to stay on the island with her son. One day as she innocuously went into a grocery shop her eyes met Leonard Cohen’s gaze. They immediately connected and he invited her to come and sit with him and his friends. This was the beginning of their loving relationship, which lasted under various guises until the rest of their lives.

Far from an anachronistic take on the association of an artist and his muse, which has fuelled the collective appreciation of Marianne and Leonard’s relationship and shaped their intertextual personas, the film offers an authentic account of a never ending love story and an insight into the multi-faceted personalities of Marianne and Leonard, the different roles which they had to take during the course of their lives and the multiple ways in which they influenced each other and their surrounding environments.

“When I wake up in the morning the only thing that concerns me is whether I am in a state of grace or not” the poet and writer Leonard Cohen states in a TV interview in the 1960s, in one of the first sequences of the film. Like many of his contemporaries the writer would wake up early in the morning in order to utilise a state of creative flow, after “the muse” had visited him, in order to translate his inspiration into words, meanings and characters. To say that Marianne was Leonard’s muse is just too simplistic an association. Hydra was Leonard’s muse; all the local fishermen and artists he interacted with every day were his muse; the eerie stillness of an island without cars, electricity or running water was his muse; the spirit of 1960’s movements were his muse.

Marianne was much more than the stimuli for him to tap into his creativity. A person so close to him, who both inspired and nurtured his artistic vision, Marianne was also a force to be reckoned with when it came to helping the people she cared about find their distinctive voice. She was the one who persuaded Nick Broomfield to make his first film. She was the one who motivated Leonard Cohen to keep writing after his first novel “Beautiful Losers” was panned by critics at the time of its publication and he suffered a breakdown. Their multi-layered connection extended far beyond the confines of any particular definition.

Marianne and Leonard kept communicating and seeing each other, as much as possible, after he left Hydra to pursue a music career in LA. They gradually drifted apart after a few traumatic incidents transpired, coinciding with the decadence of the artistic community in Hydra, the requirements and lifestyle of a professional career in the global music industry, which Cohen had to adopt. There is a sense that the entire period in Hydra was a time of escapism for Leonard, Marianne, little Axel, the entire community as evidence in the film suggests. Soon after a period of great creativity, inspiration and cultural exchanges all the hedonistic, acid-fuelled days and nights suddenly weighed too much on the shoulders of the international residents of Hydra. Or their effect just wore off and they had no option but to return to their unresolved issues and psychological traumas.

Even though the film clearly illustrates that this is the case for a few members of the community, there is not enough information to make a safe assumption about Marianne. The film leaves out a detailed account of her background in Norway and apart from some sequences regarding a couple of visits she made to Broomfield in England, it becomes more focused on Cohen’s career and personal life, after the time in Hydra. It is almost as if Marianne blends into the background of other character’s stories which prevent her persona to be fully developed. Conscious or not, the omission of Marianne’s voice reflects an imbalance which might be attributed to lack of resources or the possibility that perhaps Nick Broomfield was too involved to document the pain and of a person he felt so close to. However, the balance is gloriously restored towards the end of the film, which proves that the filmmaker wisely followed the route of maintaining Marianne’s mesmerising, mysterious aura by highlighting her virtues and attributes through her impact on others.

Broomfield’s personal involvement, which permeates all narrative levels essentially driving the film, allows us to get a real sense of the 1960s zeitgeist and the personalities of the protagonists who sometimes appear to blend into the scenery of Hydra or the lives and art of others, in the case of Marianne. Developing on two levels, namely the narration of Marianne and Leonard’s love story and the use of autobiographical elements to highlight the effect which the latter had in Broomfield’s life and career, the film emanates a strong sense of authenticity. Having been a close friend and long-time observer of the tumultuous love affair on the one hand and the development of their complexity of their characters on the other, Broomfield is very well versed to give a creative testimony of the events and behaviours which shaped the personalities of the people en-route to becoming the great artists and personas which the world has come to know and admire. That been said there is a feeling that this biased approach leads the filmmaker to employ all means available in order to convey his personal opinion of the characters with regards to their emotional state, dreams and aspirations. Since he is himself a character in this film however, it is easy to distinguish the deep admiration, respect love and potential jealousy driving his choices.

In any case, the film’s biggest contribution to the legacy of this widely documented, glorified and timeless love story is that it doesn’t just present the connection of two tremendously charismatic people through incidents, love letters, love songs and accounts of the people immediately involved. It also maps a more nuanced and complex association by highlighting the impact that this relationship had to the immediate and extended environment of theirs. Most importantly, the tender and kind way in which this manifests itself make this film a unique emotional experience, as if discovering a long lost family photo album and exploring the stories of all the people depicted. It is love re-defined and they own it.

By Eirini Nikopoulou.

Info: Marianne & Leonard: Words Of Love. Genre: Documentary. Filmmaker: Nick Broomfield. Producers: Nick Broomfield, Mark Gibbon, Marc Hoeferlin, Shani Hinton. Original Music: Nick Laid-Clowes. Camera: Barney Broomfield.

The film is available in UK cinemas from Friday 26 July.