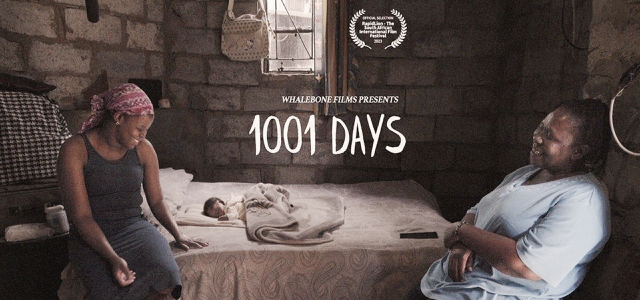

A red-eye flight from London brought me to Oliver Tambo International airport in Johannesburg as a guest of the 9th RapidLion South African International Film Festival in March 2023 and one of the first and most captivating films I caught was the feature length South African/UK documentary 1001 Days.

Set in Johannesburg, the film follows a group of dedicated women attempting to nurture and support vulnerable young women as they traverse through pregnancy and early childbirth over the course of one thousand and one days, the length of time suggested as being the optimum time for the physical and psychological development of babies. Parents too- it’s also the most difficult time for young pregnant women trying to bond with their babies, especially for those living in the toughest of social conditions where they constantly battle poverty, drug addiction and violence.

The film starts abruptly in un-ceremonial fashion in a tiny, brick-walled bedroom. A nervous, quietly spoken young woman is comforted by a motherly type, intently listening for any hopeful murmur. But there’s very little of that, her partner has disappeared, she has no job, no money and is well into her pregnancy. The promise of “Don’t worry, I’m here to support you” falls hollow as the woman talks of suicidal thoughts. It’s a long, ambling take. Then the nervous young woman suddenly bows her head, wipes at a tear and the matriarch, who we discover is Thandiwe, a home visitor from Ububele, a Women’s charity group based in the Alexandra Township, tenderly reaches out a consoling hand. The camera holds its nerve. Then as the tears flow, Thandiwe moves in to hug the distressed woman. It’s a humbling sight. When we do cut, it’s to Thandiwe, now outside the dwelling, standing alone on a balcony, consoling herself with a cigarette whilst padding at her own silent tears, no doubt at the misery of her charge. In the background, the swell of the Alexandra township looms large.

We meet the home visitors from Ububele, all local women who we discover shared similar experiences in their youth, teenage pregnancies and the prospect of facing a hard world alone. Only that was then. Today, thirty years after the end of apartheid, with a tsunami of social problems sweeping urban areas, soaring mental health issues are being ignored. Yet there is hope, as demonstrated by these women through Ububele ('compassion' in English) an organisation in its twenty third year that strives to maintain its goal of helping children born in poverty to grow into emotionally healthy adults. The women meander through tiny streets and alleys, seeking out lonely pregnant women, as much as twenty a day, some as young as fifteen, making sure they attend medical checkups and feed themselves and their babies. Bonding with their babies is an important element in their support, “Do you speak to your baby?” Thandiwe asks one young, carefree woman. “But he cannot speak to tell me what he wants”, came the innocent reply.

It’s clearly not easy cajoling the irreverent youth of today who grew up waiting for freedom to give them a better life after Apartheid’s defeat. But these patient women from Ububele, determined to improve their community, battle on through the mire. A woman worries that her baby will become a crux for a miserable life. She had grown up knowing that her own mother had killed herself and now appears to bear that trauma with repeated visions of the mother she doesn't remember. Another woman frustratedly laments on the unfairness of the justice system after the case against a local man accused of kidnapping, assaulting and allegedly raping her young daughter was released due to the ineffectiveness of his arresting officer who, it turns out, retrieved DNA tests from witnesses but failed to get one from the accused. "We don't trust men", states a local erstwhile young woman as she attempts to explain the breakdown in community relations. So how does society protect its vulnerable girls and women? The historical evolution of the townships appears to leave a distrust of state services. One such, a clearly sick woman is reluctant to go to the hospital for the medication she needs to get well. “It’s just this flu”, she says. When we catch up with her later in the film, she is bedridden, her almost two year old toddler plays in the bed beside her as she struggles for breath while writhing in pain. It was pitiful.

1001 Days is a thoroughly engrossing and claustrophobic documentary extrapolating personal testimony with sometimes excruciating honesty. Directors, Kethiwe Ngcobo and Chloe White allow the camera’s shaky, shiftiness in the early sequences to seamlessly segue to a taut stillness later on, impressively utilising natural space to elicit sensitive information from their subjects, whilst remaining unobtrusive- not so much ‘fly on the wall’, but more silent elephant in the living room’. There seemed to be an almost cinematic aesthetic to this ‘domestic’ documentary with Catherine Meysburgh’s wonderfully timed editing - noted not for its cutting, but for knowing when not to cut, in sequences that episodically move each story along in an engaging, non sentimental fashion- there’s enough emotion in the circumstances of these young women- that serves the theme and message with clarity.

Besides the inherent quality of the filmmaking the film throws up a most apposite conundrum... the role of men in South African Society, particularly amongst the working class and begs the question: where are they, these fathers, these progenitors of the next generation of Africa’s future? Suffice to say this quality film points to the post-apartheid trauma that black South Africans, bear from years of obstinate dehumanisation, manifestly harvested in a facile armour that in stark terms highlights how little have been the steps trod by this battle-scarred society, yet every journey starts this way.

MN

VIEW TRAILER

Read the filmmakers in their own words as co-directors, Kethiwe Ngcobo and Chloe White along with producer Rose Palmer and Nicki Dawson, a Programme Manager from Ububele tell the story about the making of this remarkable film. Read the interview here >>>>

1001 Days had its world premiere at the RapidLion South African International Film Festival and is an official selection at Sheffield Docfest 14-19 June 2023.

1001 Days | 97 mins | South Africa/UK | Whalebone Films, 2022 | Directors: Kethiwe Ngcobo, Chloe White | Editor: Catherine Meyburgh | Producer: Rose Palmer | Executive Producer: Katharine Round