I recall my schooldays in Croydon as a lean thirteen year old watching grainy 1950’s documentary footage of Stetson wearing Australians on horseback 'Abbo hunting’ in the outback. While out on expedition, these dusty, leather-skinned men would routinely poison the drinking water of rural Aboriginals.

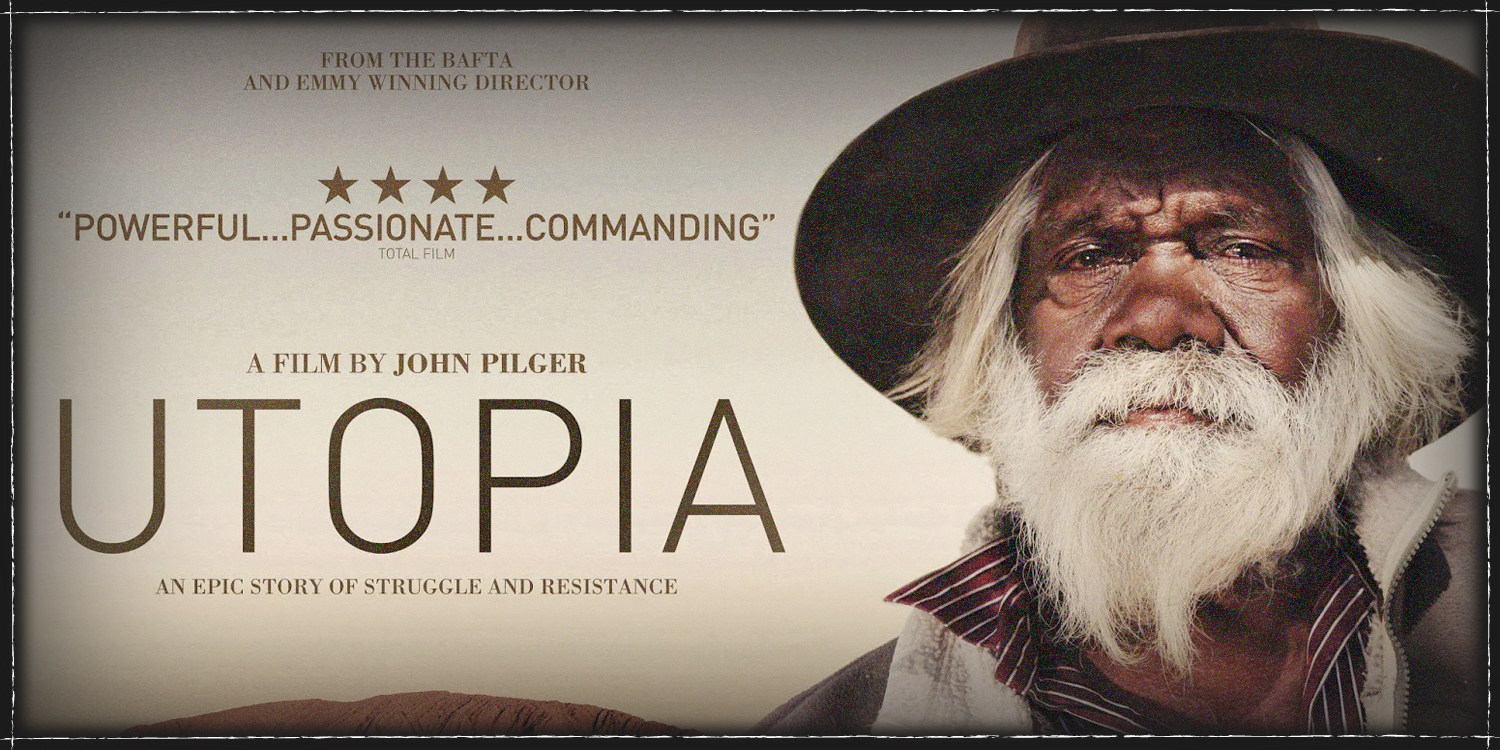

At the time I remember being confused because a little earlier that term we, of the General Studies' class had been watching similar grainy black and white film of Nazis persecuting Jews. Today, watching John Pilger’s formidable Utopia the memories come flooding back. To Australia’s shame.

Pilger’s hugely personal film tugs at the heartstrings particularly when we see the struggle of a family he first followed over thirty years ago in a somewhat futile attempt to gain justice for the death in custody of their twenty three year old son. They are still searching for that justice. Pilger highlights this problem further by showing harrowing CCTV footage of another young man brought into police custody "for his own protection" who subsequently dies alone on a police mattress in a squalid police cell. Although thousand of viewers of the film will witness this death it is as if no one is actually watching. These injustices cut deep into the history of the country, from its penal colony beginnings to its rapid commercial growth – along the way paying scant homage to its indigenous inhabitants’ nonchalantly nursing a three thousand year legacy.

What Pilger’s Utopia shows us with a hint of ‘sledgehammer’ is the subtlety of intransigence: Australian whites’ steadfast doggedness in refusing to support financially and collectively a pseudo-primitive culture and an indigenous people equally stubborn in adapting to European ways. The sad thing is that it’s a collision with only one victor. Take a backwards glance to the story of Native Americans in the United States three centuries hence as that continent embarked on a modernisation programme taking no prisoners, literally. We’re talking about thousands, if not hundreds of thousands of deaths. Australia is a huge continent with a tiny population and could easily accommodate their indigenous population but like the US in the 19th century, land is at the core of the impasse. Whereas in the US it was the building of cities to accommodate a fast growing population here it’s economics: big multinational companies needing mineral-rich land balanced against successive governmental administrations’ desire to keep the country rich. This equation was brilliantly demonstrated in a scene where a government official disguised himself to appear on a high profile news programme to expose paedophile rings at the heart of Aboriginal communities to which the government immediately launched a programme of removing children from families. The whole scenario would be laughable if it wasn’t so sinister. Before long mining companies, who purportedly pay little or no tax against massive profits, moved onto the land vacated by Aboriginal communities in the aftermath of government interference. Pilger’s film marvels at how they got away with it, particularly with clear evidence of ministerial involvement and it begs the question as to how criminal proceedings haven’t yet been executed.

Ultimately, Utopia is a poignant, well-intentioned documentary, lifted by the sheer sardonic personality of its architect. However, it lacks any idea of a solution- maybe that’s the point Pilger is trying to make – can there be any thought of a solution against the unrelenting search for profit at the expense of a community who have long since given up?

By Mark